This is a very long and complicated post, so I’ll give you a few take home points up front…

Equity Center Radio on School Finance Pork: http://216.246.105.5/Audio_Recordings/2011-0053_ECRadio_Bruce_Baker_02-18-2011.mp3

Take home points

- Crude assumptions promoted by the “new normal” pundit crowd that across the board state aid cuts are a form of shared sacrifice are misguided and dreadfully oversimplified.

- State aid cuts hurt some districts and the children they serve more than others, even when those aid cuts are “flat” across districts. Districts with greater capacity will readily recover their losses (and then some) with other revenue sources. Those who can’t are out of luck.

- State aid cuts as a proportion of state aid are particularly bad because they take the most from those who need the most.

- Some might find it surprising that many state school finance formulas contain special provisions that allocate relatively large sums of aid to very affluent school districts – districts that could easily pay for the difference on their own and serve relatively low need student populations. One can readily identify hundreds of millions of dollars in New York State being allocated as aid to some of the nation’s wealthiest school districts.

- State legislators and Governors often protect this aid – which I refer to as school finance PORK – even while slashing away disproportionately at aid for the neediest districts.

- That’s just wrong!

Now for the lengthy post…

It’s budget proposal and state-of-the-state time of year right now. And Governors from both parties are laying out their state budget cuts, many refusing to consider any type of “revenue enhancements” (uh… tax increases). These include New York’s Governor Cuomo suggesting a 7% cut to state aid.

There exists a baffling degree of ignorance being spouted by pundits about school budget cuts. Stuff like – NY’s Governor cut school funding by 7%… Now, school districts need to figure out how to cut their spending by 7%! Everyone, 7% less, across the board! Shared sacrifice! It will make everyone better and more efficient in the long run (especially those high poverty districts that we know are least efficient of all)! Pundits argue – Cuts have to be made. Cuomo’s cuts are a perfect example of this reality (from a Dem. Governor). Everyone will be cut. Just suck it up and learn to deal with the New Normal.

Wrong – at so many levels it’s hard to even begin explaining reality to those pundits who’ve clearly never even taken the most basic course on public finance or public school finance and have absolutely no understanding of the interplay between “local” property tax revenues and state aid, or the process of school budget planning and adoption. More on this later.

Thankfully, most readers of my blog and many in the general public actually seem to understand this stuff better than the blowhards (bloghards and tweethards) leading the “new normal” campaign from their DC think tanks. Particularly astute are those families with children who have interest in the quality of their local public schools and live in states where local school district budget setting remains at least partially an open public budgeting process.

And there a few good education writers out there who have developed a solid grip on the interplay between state and local revenues and the resulting effects of state aid cuts. Meghan Murphy, in the Hudson Valley in New York State has done some particularly nice writing on the topic: http://www.recordonline.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20100426/NEWS/100429738

My reason for this post is to expand on a point made by Meghan Murphy in her writing on Hudson Valley Districts and by David Sciarra in this Education Week Article:

But David G. Sciarra, the executive director of the Education Law Center, argued that if states cut funding to school districts during this difficult financial period, the pain will be felt most by disadvantaged students. Impoverished districts have little local property-tax wealth to draw from, and so state aid is a lifeline, said Mr. Sciarra, whose Newark, N.J.-based group advocates for poor students and schools. He urged state officials to work cooperatively with districts in the years ahead to set budget priorities so that current inequities aren’t made worse.

State officials “have an obligation to look for better ways to spend money,” Mr. Sciarra said, but “they’ve got to be very careful in how they do this. Across-the-board cuts and freezes have a negative impact on schools in need.” Ideas about how to cut spending are often proposed at “30,000 feet,” he said, but officeholders need to “take a serious look at how [cuts] would play out in their state.”

Yes, that’s the point. Cuts don’t mean “cuts” or “across the board” uniform distribution, “shared sacrifice,” at least not as they are typically implemented. In general, cuts to state aid lead to increased inequity. They hurt some more than others. Some districts, in fact, have little problem overcoming cuts – rebalancing their budgets, while others, well, to put it simply – are screwed. In many states, those most screwed by aid cuts are those who’ve been most screwed all along.

The model underlying local school budgets is that local voter/citizen/parent/homeowners (not entirely overlapping) desire a certain level or quality of schooling, usually in tangible terms like class sizes or specific programs they wish to see in their schools. That is, the local voter may not be able to “guess” the per pupil expenditure of their district (nor is it particularly relevant if they can) and evaluate whether it’s enough, too much or too little, but the local voter can evaluate whether that per pupil dollar buys the programs and services – and class sizes that voter wants to see in his/her local school district and whether they are willing to add another dollar to that mix.

When the state cuts aid to local school districts the usual first local response is to figure out how to raise at least an equal sum of funding – plus additional funding to accommodate increased costs – so as to maintain the desired schooling (class sizes, programs, etc.). Few local voters seem to really want to cut back service quality. Depending on the state (or type of district within the state), district officials put together a budget requiring a specific amount of revenue – which in turn dictates the property tax rate required to raise that revenue – given the state aid allotted – and then the budget is approved by referendum – or other adoption (or back-up mediation) process.

Clearly some communities have much greater capacity than others to offset their state aid losses with additional local revenues!

For example, when New Jersey handed down state aid cuts to 2010-2011 school budgets and when- for the first time in a long time- the majority of local district budgets statewide failed to achieve approval from local voters, it was still the case that the vast majority (72%) of local budgets passed in affluent communities – in most cases raising sufficient local property tax resources to cover the state aid cuts. In another case, local residents in an affluent suburban community raised privately $420,000 to save full day kindergarten programs. Meghan Murphy’s analysis of Hudson Valley school districts shows that New York State districts also have attempted to counterbalance state aid cuts with property tax increases, but that the districts have widely varied capacity to pull this off. Parents in a Kansas district are suing in federal court requesting injunctive relief to allow them to raise their taxes for their schools (they use faulty logic and legal arguments, but their desire for better schools should be acknowledged!)

Distribution of State Sharing

There’s a bit of important background to cover here. State aid formulas drive state funding – usually from income and sales tax revenues collected to the state general fund – out to local public school districts based on a number of different factors. Typically these days, state funding formulas start with a calculation of the amount of money – state and local – that should be available at a minimum in order to provide adequate public schools. That is, each district is assigned a target amount of state and local funding. That target amount usually varies by the types of students served in a district and by other factors such as regional labor costs and remote, rural locations. In any case, each district ends up with a different estimate of total funding needs.

Next, the aid formula includes a calculation of the amount of that funding target that should be paid for with local property taxes – a local fair share, per se, or local contribution. One approach is to determine how much each district would raise if each district adopted a uniform property tax rate. For those districts that raise more than their target funding with that tax rate alone, the state would kick in nothing. For those districts that implement the local fair share tax rate and still come up short of their target funding, the state would apply aid to cover the difference.

So, for example, you might have three districts in a state, where:

- The first district has a very low need student population (almost all from affluent, educated families), and has significant taxable property wealth. That district might have a target funding per pupil of $10,000, and might be able to raise all of it with an even lower tax rate than would be required. In fact, if they put up the local fair share tax rate, they might raise $20,000 per pupil. And the school finance system might allow them to do that.

- A second, “middle class” district that has a modest share of children in poverty in the district, leading to an estimated target funding of $12,000 per pupil. The district adopts the local fair share tax rate and raises $8,000. The state allocates the additional $4000.

- And the third district, a high need district with weak property tax base, might end up with an estimated target funding of $15,000 per pupil and after adopting the local fair share tax rate only raises $2,000 per pupil, so the state allocates $13,000.

THAT’S THE BASIC STRUCTURE OF A ‘FOUNDATION AID’ FORMULA!!!!

Now, I should be very clear here that the relationship between student needs and tax base is not really that simple. Both parts of this puzzle are critical to the formula and don’t always move in concert. There exist districts with high value tax base and high need student population and vice versa, and for many reasons.

Here’s an example of the distribution of the basic “sharing ratio” for New York State school districts, with respect to district Income/Wealth (IWI) ratio. For the lowest income/wealth districts, the state share is about 90%. For wealthier districts, that ratio – in theory – drops to 0.

Figure 1: NY State Sharing Ratio by District Income/Wealth

Types of Cuts

When it comes to state aid cuts, there’s really nothing for the state to cut from the first district above – that is – unless for some reason the state is giving other money to that district that can raise double it’s need target with the same local tax rate and no state support. But that would be silly, right? More later on that. Here are the two most common approaches to handing out cuts:

Option 1: Cut state aid proportionately across the board

This is actually usually the worst option and most regressive. Let’s take our districts above. A 5% cut to state aid for our first district is, of course, nothing. A 5% cut for our middle class district is $200 per pupil. A 5% cut to state aid for our high need district is $650 per pupil. Yes – the biggest cut comes down on the highest need district.

This distribution of cuts is problematic for two reasons. First, the biggest cut falls on the neediest kids. Second, the biggest cut falls on the district with the least capacity to offset that cut. I’m assuming here that these districts have all adopted the local fair share property tax rate. That rate only raises $2,000 per pupil in revenue for the high need district whereas the same rate raises 4X as much in the middle class district. Clearly for this reason alone, even if the cuts were in equal amounts per pupil, the middle class district would have a much easier time replacing the aid cut with local resources. Further, there a plethora of additional factors that increase the likelihood that the middle class district can offset the cut more easily than the high need, low-income district.

Option 2: Cut funding targets proportionately across the board

A better, though still problematic approach is for the state to recalculate the funding targets – – to reduce that level by just enough to result in the same state aid savings. Taking this approach leads to a constant per pupil cut in state aid across districts, for those districts receiving at least as much state aid per pupil as is being cut.

This too is of no consequence for our district that needs no foundation aid. Let’s say this approach leads to a $400 per pupil across the board reduction in target funding. If we still assume that districts are to raise the same amount of local revenue (local fair share of the fully funded target amount, as opposed to raising the local share of the lowered amount), this would result in a 10% aid cut to the middle class district ($400/$4000) and a 3.1% cut to the high need district. The per pupil target funding change would be the same. But the middle class district would certainly complain that their cut as percent of aid is much larger. But again, that district has 4X the local revenue raising capacity on a dollar per pupil basis, and in this case, they still got less than 4X the per pupil cut.

Even this approach is likely to lead to larger average budget reductions in higher need districts.

Again, there are tons of additional factors involved, and various ways that states might cut aid differently to yield different distributional effects across districts.

State Aid Formulas have Lots of Parts! Some better than others!

The state aid cut scenarios presented above assume a logical and oversimplified world of state aid and local district budgets in many ways. The cut scenarios presented above adopt one really big assumption about state aid to local schools – an assumption that may not be and usually isn’t entirely true:

That the only state aid available to cut is aid that is allocated in proportion to wealth and need across districts. That because state aid is allocated in greater proportion – if not almost in its entirety to poor and need school districts, then those districts must necessarily suffer most from the cuts! As a result, the best you can do is to spread evenly those cuts across wealthy and poor, higher and lower need districts and live with the fact that some will bounce back easier than others.

The fact is that state aid formulas may at their core be built on a seemingly logical foundation funding structure with state and local sharing as described above. But rarely these days does a state aid formula make it into law without a multitude of adjustments and other PORK added on. Yes, Pork! School finance pork and lots of it. Clearly state reps from those towns that would otherwise get nothing from the general aid formula are going to search for a way to bring home some pork.

Here are a few examples of school finance pork from the New York State school finance formula:

1) Minimum Foundation Aid: Like many state funding formulas, even though the first (and most logical) iteration of calculations for estimating the district state share of funding would end up providing 0% state aid to many districts, those formulas include a floor of funding – a minimum guarantee of state aid. That’s right, even our district above that could raise double their target funding by applying the local fair share tax rate would get something. Perhaps this is a reasonable tradeoff when the money is there. But do we really want to keep allocating that money to a district that’s a) fine on its own and b) could easily replace the money with modest increases to local taxes – and would do so.

Here, for example, is the effect of New York State’s minimum threshold factor on foundation aid. The red diamonds indicate the foundation state aid that would be received if districts got what is initially calculated to be their state share. State share hits 0 at an income/wealth index around 1.0 in the basic calculation. But, the actual calculation of state share includes a few adjustments shown in blue squares. First, between income/wealth ratios of about 1.0 to 2.0, the actual state share cuts the corner providing more gradually declining aid rather than going straight to 0. Then, above IWI of 2.0 it never hits 0, but rather levels off providing a minimum allotment of several hundred to about $1,000 per pupil to even the wealthiest districts in the state (which, by the way, are among the wealthiest in the nation!).

Figure 2: Application of Original Calculation and Adjusted Calculation for State Aid Share

Altogether, the adjustments – which also yield additional aid for New York City – add up to nearly $3.8 billion dollars. That’s right… $3.8 billion (where’s that NY Mega Millions guy when you need him?). Now, assuming that it’s hard to get the sharing ratio correct for NYC to begin with and that it is a very high need district that in fact needs this aid, it’s really just over $2.0 billion in potential excess allocation that could be redistributed. That ain’t chump change.

But let’s go really conservative here, and just look at the minimum aid being shuffled out to the richest communities. That alone is still $134 million dollars.

At the very least, if you’re going to cut state aid, cut this first! If you’re not going to cut, consider redistributing this.

2) School Tax Relief Aid: Many state aid formulas include a variety of other types of aid, some which are distributed in flat amounts across all districts regardless of need, and some which may be even allocated in inverse proportion to what most would consider needs – either local capacity related needs or educational programming and student needs. Such is the politics of school finance. For those really interested in this stuff, see the following two articles:

Baker, B.D., Green, P.C. (2005) Tricks of the Trade: Legislative Actions in School Finance that Disadvantage Minorities in the Post-Brown Era American Journal of Education 111 (May) 372-413

Baker, B.D., Duncombe, W.D. (2004) Balancing District Needs and Student Needs: The Role of Economies of Scale Adjustments and Pupil Need Weights in School Finance Formulas. Journal of Education Finance 29 (2) 97-124

New York State’s piece de resistance is a program called STAR, or School Tax Relief program. In simple terms, STAR provides state aid in disproportionate amounts to wealthy communities to support property tax relief. Here’s the distribution of STAR aid with respect to district income/wealth ratios:

Figure 3: STAR Aid per pupil and District Income/Wealth Ratio

Excluding STAR aid to NYC, the aid program in 2008-09 provided $642 million in aid to districts with an income/wealth ratio over 1.0! Even in New York State, that’s not chump change. It’s over $150 million to the wealthiest districts. Add these hundreds of millions to those above and we’re getting somewhere.

Once again, at the very least, if you’re going to cut state aid, cut this first! If you’re not going to cut, consider redistributing this.

For more information on the equity consequences of STAR (as well as simulated solutions), see: http://eus.sagepub.com/content/40/1/36.abstract

A closer look at aid to the wealthy in New York State

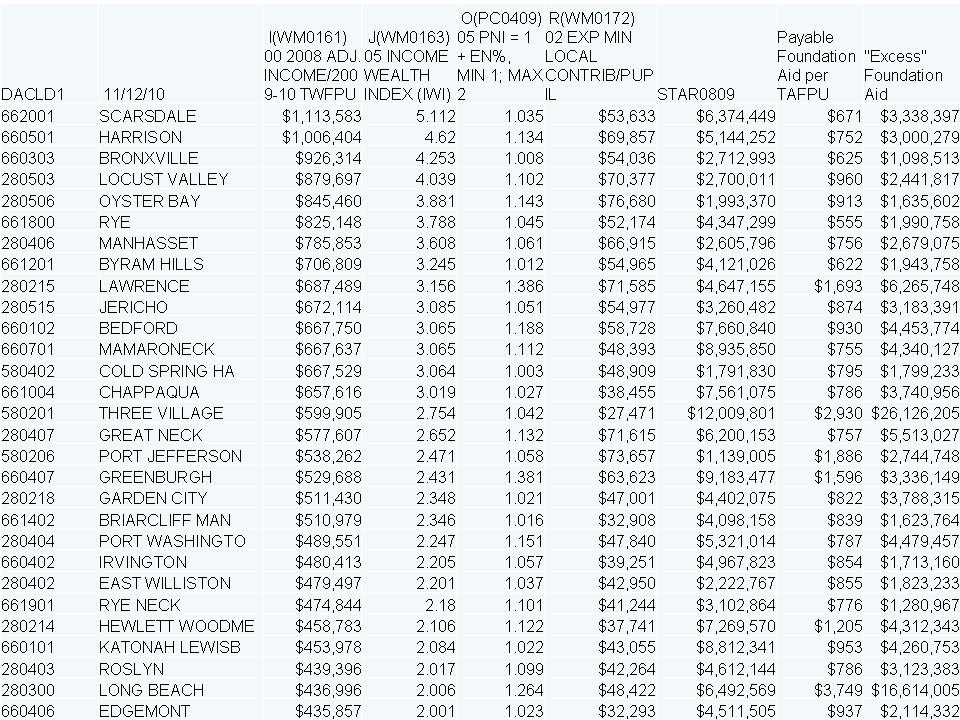

Here’s a closer look at minimum foundation aid and STAR aid received by several of the state’s wealthier communities (at least statistically wealthier). Note that our recent report on school funding fairness (www.schoolfundingfairness.org) identified New York State (along with Illinois and Pennsylvania) as having one of the most regressively financed systems in the nation. On average, low poverty districts have greater state and local revenue than high poverty ones, yet the state is still allocating significant sums of aid to low poverty districts!

Table 1: Aid to the Wealthy in New York

This table shows that many of these wealthier communities are picking up millions in STAR aid and upwards to a thousand dollars per pupil in basic foundation aid. Yes, the state is subsidizing the spending – quite significantly – of some of the wealthiest districts in the nation, while maintaining a regressive system as a whole. And now, while cutting aid disproportionately from poor districts.

The distribution of proposed aid cuts

Here is the distribution of the Governor’s proposed cuts in foundation aid to NY State school districts, on a per pupil basis, with respect to Income/Wealth Ratios of school districts:

Figure 4: Governor’s proposed cuts to foundation aid and income/wealth ratios

The income/wealth ratio is along the horizontal axis. The per pupil cuts in aid are on the vertical axis. Here, I’ve represented district size by the size of the “bubble” in the graph. New York City is the bowling ball here! And NYC gets a larger per pupil cut than many much wealthier districts – wealthy districts that actually receive aid! Excuse me, PORK!

Yes, districts with very high income/wealth ratios will experience little cut at all. $100 per pupil or so will look like a big cut of their $1000 per pupil in foundation aid, but some low wealth districts will actually see their foundation aid cut by $1000 per pupil.

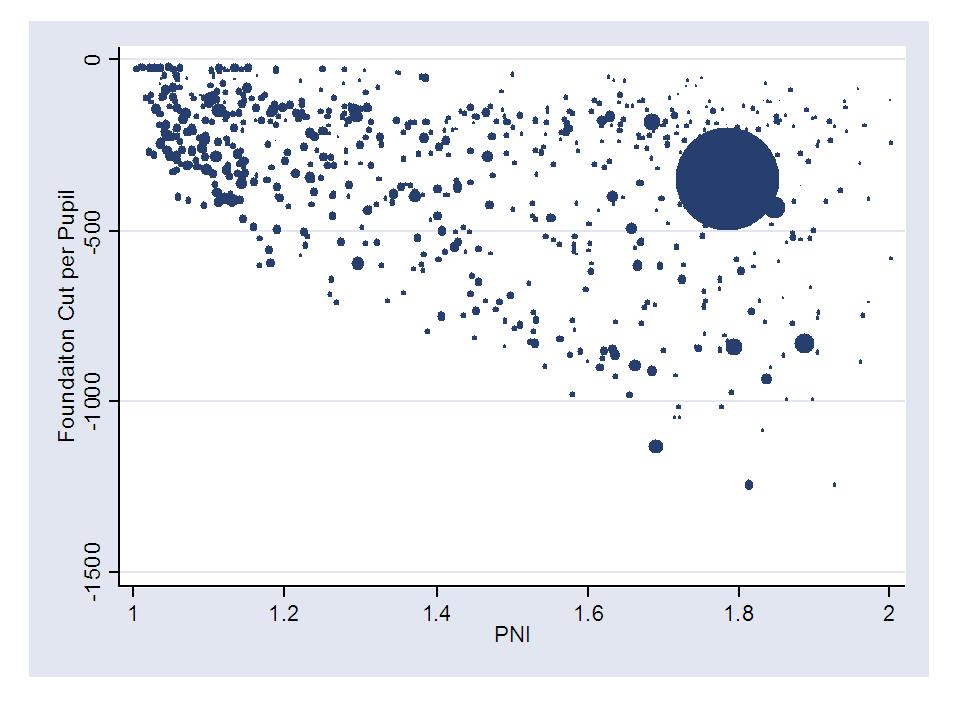

And with respect to the Pupil/Need Index:

Figure 5: Governor’s proposed cuts to foundation aid and pupil need index

In this figure, as student needs increase, per pupil cuts in aid increase. Yep, that’s right, districts that NY State itself identifies as having higher needs receive larger per pupil cuts in aid, even while the PORK… yes PORK is retained in the system! All the while, the state continues to allocate minimum foundation aid and STAR funding to wealthy districts.

Summing it up

Yes, it may suck for legislators or the Governor to tell Scarsdale, Pocantico Hills or Locust Valley that there’s just not enough aid to continue to subsidize their “tax relief” (PORK) or to subsidize their very small class sizes and rich array of elective courses and special programs with add-ons such as minimum foundation aid. But aid programs for these districts are merely the bells and whistles – or PORK – of state school finance policies, the political tradeoffs which are often needed to get a formula passed. It’s not a politically easy task, but it’s time to collect that pork and redistribute it to where it’s actually needed.

Further, it is highly unlikely that these districts will actually go without those bells and whistles – that they will forgo their furs and Ferraris. Yes, we all know that school finance formulas are a complicated mix of political tradeoffs. The goal of this post is to make that painfully clear. Let’s call it what it is – school finance Pork. And let’s take that pork and make better use of it. And let’s make it absolutely clear that protecting the pork while slashing basic needs is entirely unacceptable.

There may not be enough pork in the system to either cover all of the proposed cuts, or to be redistributed to fully resolve the funding deficits of higher need districts. But in New York State and many others, there’s quite a bit – quite a bit of aid that could be either used to make the formula fairer to begin with or to buffer the neediest districts and children they serve from suffering the most harmful and real funding cuts.

Note: On Cuts and Caps

Now, some of what I discuss herein is complicated by the current bipartisan political preference to show affluent communities that we’re not going to push these costs off onto them in the form of property tax increases – or backhanded property tax increases through state aid cuts. Instead, we’ll tell them they simply can’t raise their property taxes to cover the difference. That’ll learn ’em!

Capping property taxes while cutting state aid, is simply lying about the true cost of the programs and services desired by local citizens, who invariably have supported tax increases for their local schools and have reverted to major private giving when tax increases were not feasible. There are legitimate reasons to control local spending variation – a topic for another day – and states need to have such policy tools available. But slash-and-cap policies are generally shortsighted and ill-conceived.

Cutting and limiting property taxes merely shifts the burden in yet a different direction – increased fees, private fundraising, volunteering etc. All of which increase inequities in access to quality schooling.

Yeah, I know… all of the pundity types are saying that voters are fed up… they totally underestimate what’s being spent on their schools and they’re totally fed up with paying higher taxes. They don’t want any more of this school spending – bloated bureaucracy, etc. I might buy that if the local voter behavior in affluent communities with preferences for high quality schooling actually supported that argument. But it doesn’t!

YES! Someone rational has written about the offensive and completely inequitable approach to state funding for schools in NJ. Read the local follow up comments to the Bernards Twsp “Save Kindergarten” campaign and it is all about how unfair the cuts have been to the children of Bernards. How unfair it is that the “have to” come up with almost half a million dollars to save kindergarten when “other children” in NJ get free pre-school.

The trick, how to say that to the residents of these affluent towns. They are not actually bad people. Just blind. It doesn’t help to make them feel guilty, it will just make them defensive.

I would very much appreciate your thoughts on controlling local spending variation as well as issues related to accepting private funds for public school programs.

Where’s the pork..With the different legislative bills that are now on the table,it should be easy to determine where the pork is going.

It appears because of this new pork not only will the public school system in nj not befunded like it should be,but many individuals will not be getting the property tax relief they should be receiving.

I am just crossing my fingers that when the Special Master and then th NJ Supreme Court review all evidence presented, they will rule infavor of all public schools.I never felt SFRA was fair to begin with.From what I read,a fully funded CEIFA would have had the State pay a greater percentage of the total school budgets statewide.